![]()

![]()

![]()

■ The second half begins from here. Michurin was invited by People's Commissariat to St. Petersburg for New Year's celebrations. There, Michurin received official state certification and financial assistance for his fruit orchard from the revolutionary government ( 17~22 ).

■ As expressed in the performance of Michurin's heroic stroll through the streets of St. Petersburg ( 17 ), what is important about this sequence is that this city ( St. Petersburg ) is the symbolic place in the Russian Revolution.

■ Through Michurin's entrance ( soundtrack 4. Michurin’ Entry Moderato · Allegro non troppo · Moderato · Allegretto ), Dovzhenko again depicts St. Petersburg, where traces of the revolutionary driving force that had faded out after the capital moved to Moscow remain.

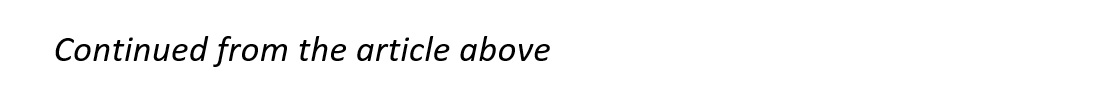

■ Michurin serves apples from his orchard to everyone and gives the speech to commemorate the fact that his orchard has been recognized as State property ( 23~26 ). However, Michurin's rivals, the scientists Kartashov and his colleagues, suspect that the new species is the product of a mere chromosomal mutation and refuse to believe that Michurin's scientific manipulation has produced the hybrid species ( 27~28 ).

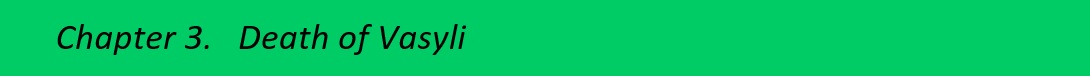

■ Michurin's comrades express frustration with the unsuccessful orchards cultivation in the cold regions of Siberia ( 29~30 ). Then suddenly Michurin comes in and tells him that Lenin is dead ( 31 ). Comrades praying to Lenin ( 32~33 ). Michurin explains how important Lenin was to the world and encourages them to recommit themselves once again to their social mission of creating orchards ( 34 ).

■ In this sequence, we can see Dovzhenko's true intention in the film, which is to depict not only Michurin's contribution to the communist society, but also the Return to Lenin through Michurin, in other words, the implicit criticism of the Stalinist regime.

■ Michurin, St. Petersburg, Lenin, and Kalinin ( to be mentioned later ), Dovzhenko emphasizes these traces of the Russian Revolution and resists Stalin, who went in the different direction than Lenin, by the artistic means of cinema.

![]()

![]()